"The Other Swedes"

~ Celebrating Them ~

~ The Smoky Valley Writers ~

Dr. Emory K. Lindquist's

1993

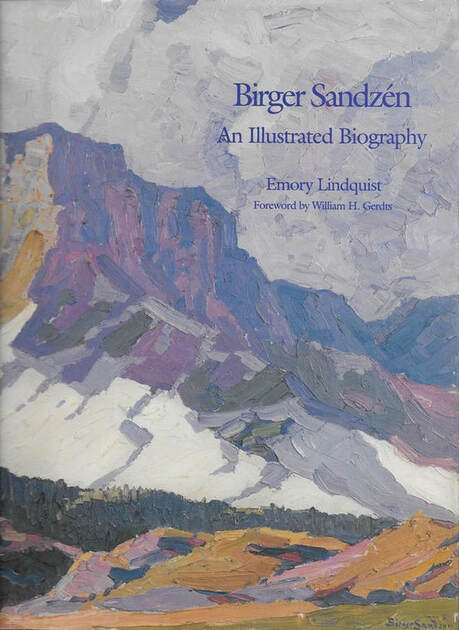

"Birger Sandzén, An Illustrated Biography"

~ "Foreword" by Dr. William H. Gerdts

~ Celebrating Them ~

~ The Smoky Valley Writers ~

Dr. Emory K. Lindquist's

1993

"Birger Sandzén, An Illustrated Biography"

~ "Foreword" by Dr. William H. Gerdts

Both the author, Dr. Lindquist, and the artist, Dr. Sandzén, were so respected by the renown, New York City resident, Dr. William H. Gerdts (1929-2020), who was a foremost authority on American art, that he gladly agreed to write this Foreword on this grand book. [William H. Gerdts - Wikipedia]

A posthumous congratulations should go out to those at the Birger Sandzén Memorial Gallery and to Dr. Lindquist who ensured that Dr. Gerdts see Sandzén's art for inclusion in his grand work composed of three volumes in 1990 titled "Art Across America," and then to invite him further to write the Foreword in the 1993 "Birger Sandzén, An Illustrated Biography."

These are the profound words of this giant on American art, Dr. Gerts, as found in his Foreword for Dr. Lindquist's "Birger Sandzén, An Illustrated Biography."

A posthumous congratulations should go out to those at the Birger Sandzén Memorial Gallery and to Dr. Lindquist who ensured that Dr. Gerdts see Sandzén's art for inclusion in his grand work composed of three volumes in 1990 titled "Art Across America," and then to invite him further to write the Foreword in the 1993 "Birger Sandzén, An Illustrated Biography."

These are the profound words of this giant on American art, Dr. Gerts, as found in his Foreword for Dr. Lindquist's "Birger Sandzén, An Illustrated Biography."

Foreword

by

Dr. William H. Gerdts

1929-2020

[Foremost authority on American Art]

--------------------------------------------

"The Art of Birger Sandzén"

by

Dr. William H. Gerdts

1929-2020

[Foremost authority on American Art]

--------------------------------------------

"The Art of Birger Sandzén"

"In the late 1980s, in preparation for my study of regional American painting, Art Across America, I've visited communities in the state of Kansas--Lawrence, Topeka, Lindsborg, and Wichita. Without question, the revelation that I sustained upon entering the Birger Sandzén Memorial Gallery in Lindsborg was not only the most extraordinary artistic encounter of the expedition but one of the most amazing and splendid first-hand experiences occasioned by the research involved with the work.

"It is intriguing to think back upon the moment, to try to recall and analyze the sensations I experienced. That revelation was not triggered simply by the appearance of Sandzén's pictures; I was already familiar with him through some of the literature I had accumulated and from a group of slides that ensured I had some idea of the artistic bold colorism--perhaps the major feature of his mature painting, as Emory Lindquist so properly emphasized in this volume. Nevertheless, I was still unprepared to find such exceptional work in a little gallery associated with a relatively rural college located in a small town in the middle of prairie land. Additional factors in the intense impression made by this display included the originality of the artist's aesthetic strategies, partly the stylistic consistency, and certainly the high level of professional quality. But I think the intensity resulted at least partially and perhaps primarily from the sense of scale of the large pictures that had been hung in one of the major rooms in the gallery.

"Sandzén's graphic work was on view also, and these prints, especially his woodcuts, are probably as phenomenal as his oils. The lithographs reflect especially the strong calligraphic manipulation of form seen in his oils, and the block prints amazingly incorporate into black and white the equivalence of the artist's color and light, which I find contemporaneously, perhaps, only in the woodcuts of the Buffalo artist, J. J. Lankes. Sandzén's block prints otherwise are quite individual for their time in America, when the primary emphasis was in the application and expression of prismatic color. Sandzén's work instead recalls the dramatic black-and-white graphics of contemporary Germans of the movement Die Brucke, though those artists concentrated upon figural and urban imaginary instead of on the landscape that so fascinated Sandzén. But I shall focus here upon the artist's oil paintings.

"As I recall, many of the works were landscapes, dramatic mountainscapes of the Rockies, and Prairie scenes of Sandzén's adopted Kansas. The artist's daughter narrated a story about her father's attraction to the local scenery, which Nina Stawski quotes in her admirable Master's thesis on Sandzén's graphic work: 'He himself documented his attraction to the colorism of the local landscape.' Emory Lindquist quotes the artist's own description of " the brilliant yellow and red along the creeks, gold Buffalo grass on the Prairie and large, bright sunflowers," but of course Sandzén's paintings are hardly transcriptive statements. And we can recognize in Sandzén's art the ultimate impact of impressionism, which the artist claimed was "the first sign of recovery. Color will no longer be an important element in painting, but an essential feature." Yet Sandzén was not an impressionist, a movement long accepted in both Europe and America by the time he achieved his artistic maturity. He was very much a modern artist.

"This was, certainly, a time-honored tradition in America for the theme of the mountain landscape, beginning with the paintings created by Albert Bierstadt after his first western trip of 1859 and continuing throughout the work he did during his subsequent journeys. The theme is found also in the pictures created by many other painters from both the East Coast and Chicago--most notably, perhaps, in Thomas Moran's work--as well as in those works produced in the second half of the nineteenth century by resident western painters. Nevertheless, though Bierstadt painted almost until his death in 1902 and Moran continued to produce variations of his earlier western subjects into the 1920s, the tradition that their work represented had been more or less discarded and critically denigrated even in the last decade or two of the nineteenth century, condemned as bombastic and grandiose on the one hand and two detailed and specific on the other. Such pictures were viewed as blatantly commercial and as too naive and characterless for a nation that, after the Civil War, had entered into a new phase of cultural cosmopolitanism.

"The sometimes exaggerated monumental (theoretically though not actually transcriptive) scenes of the Rocky Mountains were largely abandoned in favor of more poetic and even spiritual evocations of nature, in which temporal and seasonal concerns replaced the sense of place so emphasized in those earlier pictures. The generation of landscape painters led by George Inness was generally uncomfortable with mountain scenery and seldom painted it, and their successors, the impressionists, shied away from scenes of grandeur, too. The principal exception--the paintings produced by John Twachtman in the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone in September 1895--actually proves the rule, for these atypical works were never considered by critics to be the equal of the intimate landscapes that Twachtman painted in the neighborhood of his Connecticut home.

"The early 20th century, in fact, witnessed a revival of interest in mountain art, and Sandzén, through somewhat isolated from other developments in the art world and painting in a manner distinct from other practitioners, should be seen in this context. This revival occurred not at the hands of eastern visitors but of native artists-painters such as John Hafen and James Harwood, who depicted the Wasatch Mountains of Utah at the turn of the century, and especially the large group of Southern California painters of the Sierra Nevada, such as William Wendt, Edgar Payne, Jack Wilkinson Smith, Hanson Puthuff, Paul Lauritz, Benjamin Chambers Brown, and Leland Curtis.

"The Utah painters worked primarily in an impressionist-related mode. So did some of the Californians, notably Brown, but for the most part they evolved a rather distant aesthetic based upon broad, often somewhat rectangular and thickly applied brushstrokes, which yield a strong structural emphasis. The inspiration for this rather different California approach to monumental mountain scenery would seem to be the work of Paul Cézanne (although few of Cézanne's paintings were to be seen in California at the beginning of the twentieth century) and even of the cubist. Such a posited relationship is reinforced by the emphasis in the work of some of these painters--Wendt, Smith, Payne, Puthuff, and Lauritz--upon the earth colors of green and browns and in a turning away from the high key of impressionism that otherwise dominated southern California painting.

"Birger Sandzén's western paintings thus share with the work of some of his California contemporaries such qualities as a strong structural sense and a vivid fracture of paint and brush stroke, but his work differs from theirs also, notably in the rich, inventive, high-key colorism, a trademark of his mature style. This began around 1909 and 1910 with the works he created in a pointillist style, which, like those works that succeeded them, have few parallels in American art at all, let alone in a regional context.

"Sandzén is supposed to have been impressed by pointillist works and even to have worked in that manner during his six months in France in 1894. Although Swedish writers have emphasized Sandzén's pointillist affiliations, they appear to have been of short duration. Nevertheless, a number of other Americans, like Sandzén, went through a brief period of neoimpressionist divisionism, adopting the dotlike application of paint pioneered by George Seurat and continued by Paul Signac, who perhaps exercised specific influence on some of the Americans.

"This aspect of neo impressionism appears first in the work of a few Americans associated with the art colony in Giverny, France, in the early 1890s--Thomas Meteyard and Phillip Leslie Hale--though their pointillist works seem to have been created elsewhere during the 1890s as well, Hale's in Matunuck, Rhode Island, and Meteyard's in Venice and then in Scituate, Massachusetts, where he settled in 1894. Pointillism appeared again, although only briefly, around 1910 in the work of a number of young American artists besides Sandzén, including Oscar Bluemner, Joseph Stella, Thomas Hart Benton, B. J. O. Northfield, and Joseph Raphael, an expatriate living in Holland and Belgium. But pointillism did not remain a dominant mode for any of these artists for long.

"One would like to see this issue as cohesive, with these painters investigating the aesthetics of pointillism together, but in fact they were a wildly diverse group. Bluemner and Stella were both in New York City, but the former's involvement with pointillism, only a brief one in 1909, was of two short a duration to suggest any relationship with other Americans. There is little indication that Bluemner and Stella had any close association, though their work appeared together in a number of large avant-garde exhibitions. In any case, Stella's pointillism, which appeared only around 1912-1913, was perhaps the latest among these artists, and it derived from the painting of the Italian futurist Gino Severini. Nordfeldt was a Chicago painter, but his short flirtation with pointillism appears to have occurred in 1912 during a visit to Europe; this approach appears in his work painted in Venice. Benton's brief pointillist period also took place in 1910 but in the French countryside; at about the same time Raphael developed his neoimpressionist manner in the Low Countries. Raphael was, in fact, the only American to produce a sustained body of pointillist--related work, though by 1916 his art had become quite expressionistic.

"The only one of these artists with whom Sandzén shared a relationship with was the Swedish-born Nordfeldt, whom he visited in 1919 in Santa Fe; whether they were previously acquainted has not been documented. Curiously, one can trace an indirect relationship between Sandzén and Nordfeldt as well. When the latter returned to Chicago, he met the young art student Raymond Jonson in a class at the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts. Nordfeldt became an immediate influence on Jonson, and both men produced a series of vivid, full-length figure and portrait studies during the 1910s. Pointillism is not at all a factor in these paintings, though some aspects of the style do appear in Jonson's Violet Light of 1918. This may be because of an inspirational trip he took the previous summer to the Colorado Rockies, where he was tremendously impressed by both the physicality of mountain structure and the brilliance of western light, both of which Jonson captured in his Light, painted subsequently in 1917; it also incorporates pointillist qualities.

"In turn, Jonson, also of Swedish descent, became a close friend of Sandzén. Emory Lindquist suggests that they met in Santa Fe in 1918, but they surely would have known of one another earlier since Jonson's work was included in Carl Smalley's Midwest traveling exhibition beginning in 1916. Contacts among Sandzén, Smalley, and Jonson may have developed even earlier, in 1914, when Jonson's western sketching trip took him to Kansas. Although four of his pictures were shown at the Museum of New Mexico in Santa Fe in 1918, Jonson himself was not there that year; rather, he was touring in the Midwest and the Far West with a theater company presenting Ibsen's plays early in 1918, and he then spent the spring in Utah and again in Colorado. Jonson did not settle permanently in Santa Fe until 1924.

"Although Sandzén would have abandoned his brief involvement with pointillism by the time he and Jonson met, their firm friendship must certainly have been nurtured by their mutual love of western mountain scenery. During the 1920s, Jonson's paintings, under the influence of the art of Wassili Kandinsky, became increasingly abstract, but a number of them still shared with Sandzén a devotion to mountain grandeur. Meanwhile, Sandzén had evolved his mature modernist manner by 1914 if not earlier, his Wheat Stacks, McPherson County suggest a Monet subject painted by Cézanne.

"Another mutual feeling shared by Sandzén and Johnson was there love of brilliant color. Critics have continually likened Sandzén's paintings to those of Vincent van Gogh, and it is true that the earliest one- artist show of van Gogh's work took place at the Modern Gallery in New York City, roughly at the time that Sandzén developed his matured style. It is also true that the waving, curvilinear forms that Sandzén imposed especially on his cottonwood trees along the Kansas creeks do mirror the expressivity of van Gogh's treatment of foliage as does Sandzén's use of thick, heavy paint impastos, an other stylistic trademark of both painters. Although a few Americans, such as the writer Cecilia Waern, had expressed both knowledge and admiration for van Gogh's art even earlier, it seems to me that Sandzén's painting is much more related to fauvism and in fact may be viewed as an alliance between the structural concerns of Cézanne and the color intensity of Matisse and the fauves.

"In that, Sandzén was not alone. Matisse's work was exhibited in this country as early as April 1908 at Alfred's Stieglitz's 291 Gallery in New York City. A number of American painters in Paris at the end of the first decade of the century, such as Patrick Henry Bruce, Arthur Dove, John Marin, Alfred Maurer, and Max Weber, worked under the immediate influence of Matisse and were informed of Cezanne's work through the great memorial show held in the French capital in 1907. All but Bruce subsequently returned to New York City as confirmed modernists. During the early 1910s in Philadelphia, Carl Newman and H. Lyman Sayen practiced a form of fauvism in Philadelphia; Arthur B. Carles was also working there in a manner that combined the influences of Cezanne and Matisse, though his subject matter was still lifes, portraits, and later nudes, and the result were strikingly different from those of Sandzén. And the American painter Jerome Blum was exhibiting works reflecting fall colorism in Chicago in 1911.

"But the work of neither these Americans nor these French artistic forebears was readily viewable in the American heartland. Certainly many artists as well as members of the general public became especially aware of the post-impressionists including van Gogh, Cezanne and Matisse--through their appearance in the controversial study The Post-Impressionists by C. Lewis Hind, published in 1912 and much reviewed and discussed in the periodic press. It remains undetermined when and how Sandzén developed his distinct manner of landscape interpretation about this time.

"And obvious source might have been the famous Armory Show, which opened in New York City in February 1913 and subsequently went on to Chicago and Boston, as it included a substantial group of paintings by Czenne, van Gogh, and Matisse. Sandzén was certainly not averse to traveling to view major art shows--he was a visitor at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition held in San Francisco only two years later--but no documentation exists that Sandzén visited the Armory Show at one or another of its venues. Had he done, it is virtually certain that reference to such a visit would appear in his correspondence. Still, Sandzén must have been aware of some of the innovative art displayed because of the overwhelming amount of criticism and the number of reviews generated by the exhibit, but the assumption that the Armory Show what is a source for Sandzén's artistic maturation must remain speculative at this point. Interestingly, Stuart Davis, one of the artists whose work of the latter 1910s stylistically (though seldom thematically) resembles that of Sandzén, unequivocally developed his modernist stance as a result of the impact of the Armory Show.

"In addition to his western-landscape imagery, Sandzén's other major scenic focus was on the landscape of his adopted state. The Great Plains have never drawn the hordes of artists that have been attracted to the more overtly spectacular scenery of either the eastern mountain regions--the White and Green Mountains, the Catskills, the Adirondacks, the Alleghenies, and the Smokies-- or the striking western scenery of the Rockies and the Sierra Nevada, undoubtedly because of the flatter and more even prairie landscape. In addition, the landscapist active in those Midwestern states that border the great rivers --the Mississippi and the Missouri--often tended to concentrate upon those waterways. Thus, although occasional artists painted prairie scenes on their journeys west, there have been only a few specialists and these painted in regions where the river scenery was less spectacular. Interestingly, those artists who come to mind were all active roughly at the same time, during the early 20th century. This group includes the quite celebrated artists of the Canadian Midwest, Charles Jeffrey, and the South Dakota painter, Charles Green, who resided in Faulkton in the north-central part of the state, as well as Kansas painters such as Sandzén and George Melville Stone.

"The landscapes of both Jeffrey and Greener emphasize the great sweep of the prairie, its seeming endlessness and its even surface. The illimitable scenery in their paintings appears to embody a sense of optimism and promise of growth, qualities often enhanced by brilliant light and color as well as the suggestion of rich agricultural production. Although this last feature appears in some of the Kansas landscapes of Sandzén, it would seem unlikely that any contact occurred between him and either Jeffrey or Green or even that of their mutual knowledge of each other's work. Sandzén's prairie scenes are far more coloristic than theirs. Margaret Sandzén Greenough noted that her father's bright canvases were at variance with the usual regionalist imagery depicting a drab, grey, desolate land. She proposed that he incorporated a "dust" into some of his work, to which Sandzén replied, 'It'll rain again.'

"Sandzén's Kansas landscapes naturally lack the spectacular scenery of his views of the Rockies and the Southwest, but they depart from the paintings of his contemporaries by emphasizing more broken features of the Kansas landscape. Working both in Graham County in northwestern Kansas and along the Smoky Valley just west of Lindsborg, he found and recorded in his thickly rendered, coloristic style the creeks and low cliffs that monumentalize the low-lying landscape, the colorful, varied riverbank vegetation, and the swaying trees that break the horizon on his scenes along Wild Horse Creek and Red Rock Canyon. Nina Stawski perceptively speculates that Sandzén was so attracted to the Smoky Hill River and Wildhorse Creek because he had come from a land where lakes and streams were abundant to a place where water was exceptional. But at the same time, the formations at these creek beds when dry in summer prepared him, in miniature, for the canyon and mountain forms he found in Colorado and the Southwest.

"Sandzén was not alone among Kansas artists of the early 20th century in his respect for and devotion to the local scenery. The preferred subject matter of George Melville Stone was also the prairie landscape, though he was particularly concerned with it as a setting for farm activity – hence his appellation as the 'Millet of the Prairies.' Sandzén, too, did not ignore such themes, as his Wheat Stacks, McPherson County attest (quite likely a homage to Claude Monet's Grain Stacks series, to some degree). And John Noble – 'Wichita Bill' as he was nicknamed – carried with him during his expatriation in Paris and his later residency in New York City and Providencetown a sense of the endless sweep of the Kansas landscape, which served specifically as the setting for great herds of wild buffalo in his late masterwork, The Big Herd...'

"Sandzén's impact was felt by many students, those who studied with him in Lindsborg and those whom he instructed at other schools during the 1920s. Sandzén was unusual in that at these institutions he undoubtedly exerted greater influence on his pupils then the setting of those schools [college/university job offers] offered him. He was already a painter of the Rockies, and no perceptible change appears in his paintings during the Broadmoor Art Academy experiences during the summers of 1923 and 1924. This is in contrast to Robert Reid, John F. Carlson (whom Sandzén replaced as the landscape painting instructor), and later Ernest Larson, other instructors during the decade whose only paintings of mountain scenery reflect their experiences in Colorado Springs. Sandzén's impact on his students at the Broadmoor Art Academy can be seen in the work of Donna Sumner, who won the Birger Sandzén prize landscape painting in 1923 and who remained associated with Colorado Springs throughout her career, and in the art of Ada Caldwell, probably the most influential painter in South Dakota in the first half of the twentieth century.

"Sandzén's influence seems to have been even greater during his years in Logan, where he represented a unique force of modernism from outside the Utah art community. He was hired as the first of a series of visiting artists-in-residence to offer an alternative to the traditional instruction that had previously characterized art education in Utah. This impact, however, is more difficult to document, since the historical research of art in Utah has concentrated so greatly on development in and around Salt Lake City and on the relationship of the state's artistic community with the Mormon church. Nevertheless, a modernist "Logan School" appears to have developed during the 1920s, characterized by simplification of form and the introduction of strong, prismatic colors heretofore almost unknown in Utah painting.

"The dark, dramatic work of Alma Brockerman Wright, also an art instructor in Logan, gave way to a new colorism about this time. John Henry Henri Moser, who had studied with Wright in Logan from 1906 to 1908, returned there, first for one year in 1911 and again in 1929 for two decades, working in a strongly coloristic expressionistic mode. The relationships among these artists in the northern Utah city remains to be explored. Sandzén's direct influence can be seen in the work of the Utah painter, Philip Henry Barkdull, who studied with Sandzén in 1928 and 1929.

"But Birger Sandzén's significance is greater than his role as an important influence on other artists or even upon the artistic and cultural development of his adopted Kansas, as detailed in Emory Lindquist's study. The artist should be recognized, I believe, as a significant figure in the development of modernism in America in the early decades of the twentieth century. He was a painter whose perceptions of the power and dynamics of color ally him with those other Americans who have rightly being recognized as leaders in the introduction of postimpressionism in America – artist such as Arthur Dove, John Marin, Alfred Maurer, Marsden Hartley, Max Weber, and others.

"Sandzén's paintings would have qualified in style and stature for inclusion in the major exhibition held in 1986 at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, The Advent of Modernism. I suspect his omission was owing to the relative unfamiliarity of his painting, a result of Sandzén's isolation in the American heartland and the limited spread of his influence within a regional rather than a national configuration. His absence was an oversight at the time of the show, and it appears more so now that Emory Lindquist has define Sandzén so well, his life and his art. Ultimately, Sandzén's greatest and most enduring contribution is his marvelous, inimitable art."

William H. Gerdts, May 27, 1992

"It is intriguing to think back upon the moment, to try to recall and analyze the sensations I experienced. That revelation was not triggered simply by the appearance of Sandzén's pictures; I was already familiar with him through some of the literature I had accumulated and from a group of slides that ensured I had some idea of the artistic bold colorism--perhaps the major feature of his mature painting, as Emory Lindquist so properly emphasized in this volume. Nevertheless, I was still unprepared to find such exceptional work in a little gallery associated with a relatively rural college located in a small town in the middle of prairie land. Additional factors in the intense impression made by this display included the originality of the artist's aesthetic strategies, partly the stylistic consistency, and certainly the high level of professional quality. But I think the intensity resulted at least partially and perhaps primarily from the sense of scale of the large pictures that had been hung in one of the major rooms in the gallery.

"Sandzén's graphic work was on view also, and these prints, especially his woodcuts, are probably as phenomenal as his oils. The lithographs reflect especially the strong calligraphic manipulation of form seen in his oils, and the block prints amazingly incorporate into black and white the equivalence of the artist's color and light, which I find contemporaneously, perhaps, only in the woodcuts of the Buffalo artist, J. J. Lankes. Sandzén's block prints otherwise are quite individual for their time in America, when the primary emphasis was in the application and expression of prismatic color. Sandzén's work instead recalls the dramatic black-and-white graphics of contemporary Germans of the movement Die Brucke, though those artists concentrated upon figural and urban imaginary instead of on the landscape that so fascinated Sandzén. But I shall focus here upon the artist's oil paintings.

"As I recall, many of the works were landscapes, dramatic mountainscapes of the Rockies, and Prairie scenes of Sandzén's adopted Kansas. The artist's daughter narrated a story about her father's attraction to the local scenery, which Nina Stawski quotes in her admirable Master's thesis on Sandzén's graphic work: 'He himself documented his attraction to the colorism of the local landscape.' Emory Lindquist quotes the artist's own description of " the brilliant yellow and red along the creeks, gold Buffalo grass on the Prairie and large, bright sunflowers," but of course Sandzén's paintings are hardly transcriptive statements. And we can recognize in Sandzén's art the ultimate impact of impressionism, which the artist claimed was "the first sign of recovery. Color will no longer be an important element in painting, but an essential feature." Yet Sandzén was not an impressionist, a movement long accepted in both Europe and America by the time he achieved his artistic maturity. He was very much a modern artist.

"This was, certainly, a time-honored tradition in America for the theme of the mountain landscape, beginning with the paintings created by Albert Bierstadt after his first western trip of 1859 and continuing throughout the work he did during his subsequent journeys. The theme is found also in the pictures created by many other painters from both the East Coast and Chicago--most notably, perhaps, in Thomas Moran's work--as well as in those works produced in the second half of the nineteenth century by resident western painters. Nevertheless, though Bierstadt painted almost until his death in 1902 and Moran continued to produce variations of his earlier western subjects into the 1920s, the tradition that their work represented had been more or less discarded and critically denigrated even in the last decade or two of the nineteenth century, condemned as bombastic and grandiose on the one hand and two detailed and specific on the other. Such pictures were viewed as blatantly commercial and as too naive and characterless for a nation that, after the Civil War, had entered into a new phase of cultural cosmopolitanism.

"The sometimes exaggerated monumental (theoretically though not actually transcriptive) scenes of the Rocky Mountains were largely abandoned in favor of more poetic and even spiritual evocations of nature, in which temporal and seasonal concerns replaced the sense of place so emphasized in those earlier pictures. The generation of landscape painters led by George Inness was generally uncomfortable with mountain scenery and seldom painted it, and their successors, the impressionists, shied away from scenes of grandeur, too. The principal exception--the paintings produced by John Twachtman in the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone in September 1895--actually proves the rule, for these atypical works were never considered by critics to be the equal of the intimate landscapes that Twachtman painted in the neighborhood of his Connecticut home.

"The early 20th century, in fact, witnessed a revival of interest in mountain art, and Sandzén, through somewhat isolated from other developments in the art world and painting in a manner distinct from other practitioners, should be seen in this context. This revival occurred not at the hands of eastern visitors but of native artists-painters such as John Hafen and James Harwood, who depicted the Wasatch Mountains of Utah at the turn of the century, and especially the large group of Southern California painters of the Sierra Nevada, such as William Wendt, Edgar Payne, Jack Wilkinson Smith, Hanson Puthuff, Paul Lauritz, Benjamin Chambers Brown, and Leland Curtis.

"The Utah painters worked primarily in an impressionist-related mode. So did some of the Californians, notably Brown, but for the most part they evolved a rather distant aesthetic based upon broad, often somewhat rectangular and thickly applied brushstrokes, which yield a strong structural emphasis. The inspiration for this rather different California approach to monumental mountain scenery would seem to be the work of Paul Cézanne (although few of Cézanne's paintings were to be seen in California at the beginning of the twentieth century) and even of the cubist. Such a posited relationship is reinforced by the emphasis in the work of some of these painters--Wendt, Smith, Payne, Puthuff, and Lauritz--upon the earth colors of green and browns and in a turning away from the high key of impressionism that otherwise dominated southern California painting.

"Birger Sandzén's western paintings thus share with the work of some of his California contemporaries such qualities as a strong structural sense and a vivid fracture of paint and brush stroke, but his work differs from theirs also, notably in the rich, inventive, high-key colorism, a trademark of his mature style. This began around 1909 and 1910 with the works he created in a pointillist style, which, like those works that succeeded them, have few parallels in American art at all, let alone in a regional context.

"Sandzén is supposed to have been impressed by pointillist works and even to have worked in that manner during his six months in France in 1894. Although Swedish writers have emphasized Sandzén's pointillist affiliations, they appear to have been of short duration. Nevertheless, a number of other Americans, like Sandzén, went through a brief period of neoimpressionist divisionism, adopting the dotlike application of paint pioneered by George Seurat and continued by Paul Signac, who perhaps exercised specific influence on some of the Americans.

"This aspect of neo impressionism appears first in the work of a few Americans associated with the art colony in Giverny, France, in the early 1890s--Thomas Meteyard and Phillip Leslie Hale--though their pointillist works seem to have been created elsewhere during the 1890s as well, Hale's in Matunuck, Rhode Island, and Meteyard's in Venice and then in Scituate, Massachusetts, where he settled in 1894. Pointillism appeared again, although only briefly, around 1910 in the work of a number of young American artists besides Sandzén, including Oscar Bluemner, Joseph Stella, Thomas Hart Benton, B. J. O. Northfield, and Joseph Raphael, an expatriate living in Holland and Belgium. But pointillism did not remain a dominant mode for any of these artists for long.

"One would like to see this issue as cohesive, with these painters investigating the aesthetics of pointillism together, but in fact they were a wildly diverse group. Bluemner and Stella were both in New York City, but the former's involvement with pointillism, only a brief one in 1909, was of two short a duration to suggest any relationship with other Americans. There is little indication that Bluemner and Stella had any close association, though their work appeared together in a number of large avant-garde exhibitions. In any case, Stella's pointillism, which appeared only around 1912-1913, was perhaps the latest among these artists, and it derived from the painting of the Italian futurist Gino Severini. Nordfeldt was a Chicago painter, but his short flirtation with pointillism appears to have occurred in 1912 during a visit to Europe; this approach appears in his work painted in Venice. Benton's brief pointillist period also took place in 1910 but in the French countryside; at about the same time Raphael developed his neoimpressionist manner in the Low Countries. Raphael was, in fact, the only American to produce a sustained body of pointillist--related work, though by 1916 his art had become quite expressionistic.

"The only one of these artists with whom Sandzén shared a relationship with was the Swedish-born Nordfeldt, whom he visited in 1919 in Santa Fe; whether they were previously acquainted has not been documented. Curiously, one can trace an indirect relationship between Sandzén and Nordfeldt as well. When the latter returned to Chicago, he met the young art student Raymond Jonson in a class at the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts. Nordfeldt became an immediate influence on Jonson, and both men produced a series of vivid, full-length figure and portrait studies during the 1910s. Pointillism is not at all a factor in these paintings, though some aspects of the style do appear in Jonson's Violet Light of 1918. This may be because of an inspirational trip he took the previous summer to the Colorado Rockies, where he was tremendously impressed by both the physicality of mountain structure and the brilliance of western light, both of which Jonson captured in his Light, painted subsequently in 1917; it also incorporates pointillist qualities.

"In turn, Jonson, also of Swedish descent, became a close friend of Sandzén. Emory Lindquist suggests that they met in Santa Fe in 1918, but they surely would have known of one another earlier since Jonson's work was included in Carl Smalley's Midwest traveling exhibition beginning in 1916. Contacts among Sandzén, Smalley, and Jonson may have developed even earlier, in 1914, when Jonson's western sketching trip took him to Kansas. Although four of his pictures were shown at the Museum of New Mexico in Santa Fe in 1918, Jonson himself was not there that year; rather, he was touring in the Midwest and the Far West with a theater company presenting Ibsen's plays early in 1918, and he then spent the spring in Utah and again in Colorado. Jonson did not settle permanently in Santa Fe until 1924.

"Although Sandzén would have abandoned his brief involvement with pointillism by the time he and Jonson met, their firm friendship must certainly have been nurtured by their mutual love of western mountain scenery. During the 1920s, Jonson's paintings, under the influence of the art of Wassili Kandinsky, became increasingly abstract, but a number of them still shared with Sandzén a devotion to mountain grandeur. Meanwhile, Sandzén had evolved his mature modernist manner by 1914 if not earlier, his Wheat Stacks, McPherson County suggest a Monet subject painted by Cézanne.

"Another mutual feeling shared by Sandzén and Johnson was there love of brilliant color. Critics have continually likened Sandzén's paintings to those of Vincent van Gogh, and it is true that the earliest one- artist show of van Gogh's work took place at the Modern Gallery in New York City, roughly at the time that Sandzén developed his matured style. It is also true that the waving, curvilinear forms that Sandzén imposed especially on his cottonwood trees along the Kansas creeks do mirror the expressivity of van Gogh's treatment of foliage as does Sandzén's use of thick, heavy paint impastos, an other stylistic trademark of both painters. Although a few Americans, such as the writer Cecilia Waern, had expressed both knowledge and admiration for van Gogh's art even earlier, it seems to me that Sandzén's painting is much more related to fauvism and in fact may be viewed as an alliance between the structural concerns of Cézanne and the color intensity of Matisse and the fauves.

"In that, Sandzén was not alone. Matisse's work was exhibited in this country as early as April 1908 at Alfred's Stieglitz's 291 Gallery in New York City. A number of American painters in Paris at the end of the first decade of the century, such as Patrick Henry Bruce, Arthur Dove, John Marin, Alfred Maurer, and Max Weber, worked under the immediate influence of Matisse and were informed of Cezanne's work through the great memorial show held in the French capital in 1907. All but Bruce subsequently returned to New York City as confirmed modernists. During the early 1910s in Philadelphia, Carl Newman and H. Lyman Sayen practiced a form of fauvism in Philadelphia; Arthur B. Carles was also working there in a manner that combined the influences of Cezanne and Matisse, though his subject matter was still lifes, portraits, and later nudes, and the result were strikingly different from those of Sandzén. And the American painter Jerome Blum was exhibiting works reflecting fall colorism in Chicago in 1911.

"But the work of neither these Americans nor these French artistic forebears was readily viewable in the American heartland. Certainly many artists as well as members of the general public became especially aware of the post-impressionists including van Gogh, Cezanne and Matisse--through their appearance in the controversial study The Post-Impressionists by C. Lewis Hind, published in 1912 and much reviewed and discussed in the periodic press. It remains undetermined when and how Sandzén developed his distinct manner of landscape interpretation about this time.

"And obvious source might have been the famous Armory Show, which opened in New York City in February 1913 and subsequently went on to Chicago and Boston, as it included a substantial group of paintings by Czenne, van Gogh, and Matisse. Sandzén was certainly not averse to traveling to view major art shows--he was a visitor at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition held in San Francisco only two years later--but no documentation exists that Sandzén visited the Armory Show at one or another of its venues. Had he done, it is virtually certain that reference to such a visit would appear in his correspondence. Still, Sandzén must have been aware of some of the innovative art displayed because of the overwhelming amount of criticism and the number of reviews generated by the exhibit, but the assumption that the Armory Show what is a source for Sandzén's artistic maturation must remain speculative at this point. Interestingly, Stuart Davis, one of the artists whose work of the latter 1910s stylistically (though seldom thematically) resembles that of Sandzén, unequivocally developed his modernist stance as a result of the impact of the Armory Show.

"In addition to his western-landscape imagery, Sandzén's other major scenic focus was on the landscape of his adopted state. The Great Plains have never drawn the hordes of artists that have been attracted to the more overtly spectacular scenery of either the eastern mountain regions--the White and Green Mountains, the Catskills, the Adirondacks, the Alleghenies, and the Smokies-- or the striking western scenery of the Rockies and the Sierra Nevada, undoubtedly because of the flatter and more even prairie landscape. In addition, the landscapist active in those Midwestern states that border the great rivers --the Mississippi and the Missouri--often tended to concentrate upon those waterways. Thus, although occasional artists painted prairie scenes on their journeys west, there have been only a few specialists and these painted in regions where the river scenery was less spectacular. Interestingly, those artists who come to mind were all active roughly at the same time, during the early 20th century. This group includes the quite celebrated artists of the Canadian Midwest, Charles Jeffrey, and the South Dakota painter, Charles Green, who resided in Faulkton in the north-central part of the state, as well as Kansas painters such as Sandzén and George Melville Stone.

"The landscapes of both Jeffrey and Greener emphasize the great sweep of the prairie, its seeming endlessness and its even surface. The illimitable scenery in their paintings appears to embody a sense of optimism and promise of growth, qualities often enhanced by brilliant light and color as well as the suggestion of rich agricultural production. Although this last feature appears in some of the Kansas landscapes of Sandzén, it would seem unlikely that any contact occurred between him and either Jeffrey or Green or even that of their mutual knowledge of each other's work. Sandzén's prairie scenes are far more coloristic than theirs. Margaret Sandzén Greenough noted that her father's bright canvases were at variance with the usual regionalist imagery depicting a drab, grey, desolate land. She proposed that he incorporated a "dust" into some of his work, to which Sandzén replied, 'It'll rain again.'

"Sandzén's Kansas landscapes naturally lack the spectacular scenery of his views of the Rockies and the Southwest, but they depart from the paintings of his contemporaries by emphasizing more broken features of the Kansas landscape. Working both in Graham County in northwestern Kansas and along the Smoky Valley just west of Lindsborg, he found and recorded in his thickly rendered, coloristic style the creeks and low cliffs that monumentalize the low-lying landscape, the colorful, varied riverbank vegetation, and the swaying trees that break the horizon on his scenes along Wild Horse Creek and Red Rock Canyon. Nina Stawski perceptively speculates that Sandzén was so attracted to the Smoky Hill River and Wildhorse Creek because he had come from a land where lakes and streams were abundant to a place where water was exceptional. But at the same time, the formations at these creek beds when dry in summer prepared him, in miniature, for the canyon and mountain forms he found in Colorado and the Southwest.

"Sandzén was not alone among Kansas artists of the early 20th century in his respect for and devotion to the local scenery. The preferred subject matter of George Melville Stone was also the prairie landscape, though he was particularly concerned with it as a setting for farm activity – hence his appellation as the 'Millet of the Prairies.' Sandzén, too, did not ignore such themes, as his Wheat Stacks, McPherson County attest (quite likely a homage to Claude Monet's Grain Stacks series, to some degree). And John Noble – 'Wichita Bill' as he was nicknamed – carried with him during his expatriation in Paris and his later residency in New York City and Providencetown a sense of the endless sweep of the Kansas landscape, which served specifically as the setting for great herds of wild buffalo in his late masterwork, The Big Herd...'

"Sandzén's impact was felt by many students, those who studied with him in Lindsborg and those whom he instructed at other schools during the 1920s. Sandzén was unusual in that at these institutions he undoubtedly exerted greater influence on his pupils then the setting of those schools [college/university job offers] offered him. He was already a painter of the Rockies, and no perceptible change appears in his paintings during the Broadmoor Art Academy experiences during the summers of 1923 and 1924. This is in contrast to Robert Reid, John F. Carlson (whom Sandzén replaced as the landscape painting instructor), and later Ernest Larson, other instructors during the decade whose only paintings of mountain scenery reflect their experiences in Colorado Springs. Sandzén's impact on his students at the Broadmoor Art Academy can be seen in the work of Donna Sumner, who won the Birger Sandzén prize landscape painting in 1923 and who remained associated with Colorado Springs throughout her career, and in the art of Ada Caldwell, probably the most influential painter in South Dakota in the first half of the twentieth century.

"Sandzén's influence seems to have been even greater during his years in Logan, where he represented a unique force of modernism from outside the Utah art community. He was hired as the first of a series of visiting artists-in-residence to offer an alternative to the traditional instruction that had previously characterized art education in Utah. This impact, however, is more difficult to document, since the historical research of art in Utah has concentrated so greatly on development in and around Salt Lake City and on the relationship of the state's artistic community with the Mormon church. Nevertheless, a modernist "Logan School" appears to have developed during the 1920s, characterized by simplification of form and the introduction of strong, prismatic colors heretofore almost unknown in Utah painting.

"The dark, dramatic work of Alma Brockerman Wright, also an art instructor in Logan, gave way to a new colorism about this time. John Henry Henri Moser, who had studied with Wright in Logan from 1906 to 1908, returned there, first for one year in 1911 and again in 1929 for two decades, working in a strongly coloristic expressionistic mode. The relationships among these artists in the northern Utah city remains to be explored. Sandzén's direct influence can be seen in the work of the Utah painter, Philip Henry Barkdull, who studied with Sandzén in 1928 and 1929.

"But Birger Sandzén's significance is greater than his role as an important influence on other artists or even upon the artistic and cultural development of his adopted Kansas, as detailed in Emory Lindquist's study. The artist should be recognized, I believe, as a significant figure in the development of modernism in America in the early decades of the twentieth century. He was a painter whose perceptions of the power and dynamics of color ally him with those other Americans who have rightly being recognized as leaders in the introduction of postimpressionism in America – artist such as Arthur Dove, John Marin, Alfred Maurer, Marsden Hartley, Max Weber, and others.

"Sandzén's paintings would have qualified in style and stature for inclusion in the major exhibition held in 1986 at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, The Advent of Modernism. I suspect his omission was owing to the relative unfamiliarity of his painting, a result of Sandzén's isolation in the American heartland and the limited spread of his influence within a regional rather than a national configuration. His absence was an oversight at the time of the show, and it appears more so now that Emory Lindquist has define Sandzén so well, his life and his art. Ultimately, Sandzén's greatest and most enduring contribution is his marvelous, inimitable art."

William H. Gerdts, May 27, 1992

* * *

Go HERE for “Birger Sandzén” ~ The Words of Dr. Lindquist ~ The Preface and Acknowledgments.

* * *

This section pertaining to author Dr. Emory K. Lindquist's work has been approved by his family as of November 2, 2023.

* * *

To go to the

Birger Sandzén Memorial Gallery

click

sandzen.org.

This section pertaining to author Dr. Emory K. Lindquist's work has been approved by his family as of November 2, 2023.

* * *

To go to the

Birger Sandzén Memorial Gallery

click

sandzen.org.

* * *

"Let Us Celebrate Them"

* * *

Swedes: TheWayTheyWere

~ restoring lost local histories ~

reconnecting past to present

* * *

All color photography throughout Swedes: The Way They Were is by Fran Cochran unless otherwise indicated.

Copyright © since October 8, 2015 to Current Year

as indicated on main menu sections of

www.swedesthewaytheywere.org. All rights reserved.